In Ye Olden Times: Clarence Spinney and the Grand-Prize Guild Ham

By Mike Davis

Bridgton History Columnist

Howdy neighbor!

This past weekend, Zoe and I enjoyed several hours out to Fryeburg, in company with some old Academy friends, stuffing tickets in boxes hoping to win fame, honor, and best of all a good deal at the annual Fryeburg Academy Chinese Auction held to benefit the Senior Class’s Project Graduation. We didn’t win anything, but that’s okay, it’s for a good cause.

I can’t gripe too much; on reflection I didn’t follow strategic betting strategy. There were simply too many tempting things to win: gift cards from Bridgton Books, ski tickets for Pleasant Mountain, bread from local bakers, truly the finest of goods from seemingly over a hundred merchants up and down the Saco River Valley from Cornish to Bartlett N.H. Wouldn’t you know it, like a chump I went around putting in a ticket here, a ticket there on all the items I fancied, waited long hours until all the drawings were held, and in the end won nothing. Ah well, such is life. But, dear reader, there is another way. There is a certain way, a sure way to win if you really, really want to. I’ve participated in Chinese Auctions before, in fact I even helped run one once in grade school to fund a class trip to Washington D.C., but even so I find I can never bring myself to enter my tickets in a way guaranteed to win. Some personal flaw prevents me in the face of pure, unbridled chance. But there is a way to win, and its reliability was amply demonstrated to me in youth. This secret is what I’d like to share with you today; but first, a word about the wise old man who taught me how.

This is the story of Clarence Spinney and the Ham. In my childhood, another of the things that Bridgton Hospital used to do was hold an annual Chinese Auction, put on under the auspices of the Northern Cumberland Memorial Hospital Guild for which my grandmother volunteered her time. I have vague memories of attending these auctions, though whether it was because my grandmother worked with the Guild or simply because our whole street turned out each year I can’t now recall. Many were the prizes up for consideration, many big, expensive, worthy items were donated to auction off, and most people who went did what I still do and divided up their tickets more or less evenly among the dozen or so items you really, really want. Then, when it’s time to draw you cross your fingers, pray, and still have a poor chance of winning because everyone wants the three-night suite at the Mt. Washington Grand Resort and there’s about a million tickets in the pot diluting yours. This, dear reader, is not wisdom. What we should all be doing is what my grandmother told me our neighbor did, and please allow me now to tell you some things about him. This is what I remember of Clarence F. Spinney.

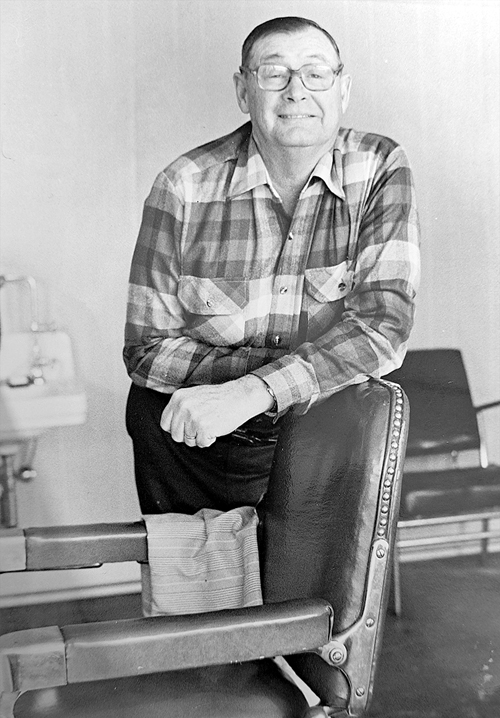

Many of our older readers will no doubt recall old Spin, Bridgton’s resident barber for some 36 years. When I was a child he lived just down High Street from my family, having retired from hair clipping around 1985. As I understand it, Spin had first come down to Bridgton from Bangor back in the days of the Great Depression, serving in the Civilian Conservation Corps stationed up on the South High Street fairgrounds where the hospital now stands. This noble group (on whom I really should say more one day) engaged in necessary forestry, construction, and general maintenance work for the state in our area, and many of the gallant CCC boys who came to Bridgton stayed on here, found wives and raised families, whose descendants are still here today. Others from this company who came to Bridgton with the CCC include Bill Foster, founder of our former Foster-Russell heating oil company, and Roy Marston, another well-loved barber who traded haircuts with Spinney for decades afterwards.

As far as Spinney’s story goes, he came to Bridgton to enlist in Company C, 1124th CCC camp around about 1938, and before long found himself a wife, Greta Chadbourne. They lived in her old family home on North High Street, opposite the old Town Hall and beside Farragut Park. In 1942, Spinney enlisted in the Army, training some two years out west at Camp Haan in the Mojave Desert, preparatory for service in the South Pacific with the 407th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion. Now any WW2 buffs out there may recognize this battalion as being the famed “Buzz Bomb Kings” of Europe, but Spinney always said that all through training his unit firmly expected they’d be sent island hopping off toward Japan. They were so sure of this that Spinney once shared his unit’s motto was “We are Never going to Europe!” But go there they did, for when at last the marching orders came down in early 1944 their destination was France, preparatory to the big D-Day invasion. “Everyone knew D-Day was coming,” Spinney once recalled, “Nobody knew when.” His convoy docked in Liverpool, England on March 11, 1944 and after briefings and more training, and the opening of D-Day itself, his unit finally crossed the channel to land at Normandy on June 22. It’s worth mentioning that fighting alongside Spinney among the 407th was a good friend of his, Toivo Kyllonen of Harrison, another of the great old-timers of our region whose wisdom, humor and character we sorely need more of these days. The stories those men could tell.

Back to Spinney, he and the 407th crossed the Channel on the HMS Battle-Axe in the immediate aftermath of D-Day, saw the smoking ruins of ships and the bodies of men lying bloated in the restless surf off Omaha Beach, and saw his First Sergeant’s foot blown off by a landmine shortly after landing American boots on the continent. Theirs was the first mobile 90mm artillery unit to reach Europe, and over the months that followed their company marched its way through northern France destroying Nazi bunkers and artillery placements. They were ordered to take the city of Brest in Brittany, site of the Germans’ largest submarine pens, and they did it, shelling warships off the coast, sinking a U-boat and battering down the city’s walls with their great guns — and the company history of their engagements pales compared to the tales old Spin could rattle off. He still kept part of the shrapnel from a German 88mm shell that landed near his foxhole one day, which had almost killed him and had done for many of his friends. He carried it in his pocket all his life.

Later, they’d been sent to Antwerp, where the 407th won their fame providing anti V-1 rocket defense to the city. Of the 2,394 German buzz bombs launched against them, Spinney’s boys knocked down 2,183 of them. Only one out of every 11 got through. He was very proud of this, and loved to detail all the strategy and cunning it took to shoot down rockets.

Returning to civilian life in Bridgton, Spinney became a barber in 1948, and until 1985 or thereabouts he cut the hair of uncounted thousands of our citizens, time and again. Of course, he never cut my hair — I’m too young for that — but even so I knew him growing up, and I have the conception that my mother, who cut my hair in house as a boy, must have learned a thing or two from him, neighbor to neighbor. He was the first man I ever knew who’d fought in World War II, and even as a young boy I had an idea of just what that meant. He’d wear his veteran’s hat often, and when I picture him one of my clearest memories puts a rifle in his hand; not his old Army M1 but a hunting rifle, because the Spinney I knew — old, retired, always smiling — loved to hunt. He’d go hunting in the woods despite his advanced age, and when he got too old to go hunting on foot he took to going out on prowls around dusk in his car, with his gun loaded and hanging down in the passenger seat beside him. He drove a great big boat of a car, an old Lincoln or Chrysler or something that they don’t make the likes of anymore, and when he’d see a deer by the side of the road that was it; he’d down the window, up gun and fire right from the driver’s seat. More often than not he’d get one, and I’d go down to see a buck tied to his hood the next morning.

He loved fishing too, and had heard enough fish stories from decades of clients in the barber’s chair that he knew how to tell a good one. If you caught a record-breaking fish, or thought you did, he’d want to see it, and when my father was teaching me to fish I’m sure I regaled old Spin with far too many childish tales of ‘it was thiiiiiiiis big’ brook trout, delivered with all the over-exuberance of youth. To his credit, he always acted impressed, waiting patiently until I was done before instantly topping my story with an even better catch of his own. He made me want to be a better fisherman. We’d go over to his house for chowder in the winters, and instead of a fridge he kept the leftovers in the barn so they’d freeze at night. It was at one of these chowder nights that he told me how he’d helped build the Sebago Lake State Park, and that seemed to me like the most impressive feat any man could ever do. When he died in 2006, the American Legion Color Guard stood salute at his funeral, and Farragut Park’s flag flew at half-staff.

I must admit I don’t know nearly enough about Spinney. I don’t know nearly as much as I feel I should; for here was an incredible man I knew, an American hero and a small-town legend who lived right next door, and now with the vantage point of maturity there are so many things I wish I could have asked him. I do know this story, and it’s the reason I thought to speak of him today. Because when it came time to wager tickets in the annual Bridgton Hospital Chinese Auction, Clarence F. Spinney knew just how to do it. You see, not every prize in a Chinese Auction has the same value. Some are big-ticket items, some are smaller ones, and a select few — items given each year by well-meaning shops as a small act of charity — are items that the vast majority of the crowd probably won’t want.

This is where the Ham comes in. Remember the Ham? I mentioned it right at the start. Because at the annual Bridgton Hospital Chinese Auction held in the old Town Hall, for decades there had appeared among the many glorious prizes every year, a giant butt of bone-in American hickory smoked Ham preserved in brine, easily on the order of a dozen pounds or more. Possibly upwards of 20, really this was truly a prodigious hunk of hog: dense, rubbery, salty, surely provided by some distant market that just plain couldn’t sell it otherwise, charitably foisted upon some sweet little old-lady of the guild who came asking for donations. However, it happened, whatever its source, every year it came. It appeared, seemingly manifesting itself, and my grandmother spoke of it in an almost mythic tone. You could count on the Ham. It was reliable. It was edible. It was slightly grotesque. But more than this, no one really wanted it. Its ticket box might only receive two or five tickets over the course of an entire day. Here was Spinney’s golden opportunity. He diligently marshaled his resources, calculated odds, and calmly focused fire on his objective.

Up he would come, his fist full of tickets, some $20, $30 or more; and carefully tearing them apart one by one he would size up the Ham, give it an appraising slap, and then proceed to stuff each and every one of his tickets in the Ham box. It was no contest. He won the Ham every year. It was his and everybody there knew it. He’d been doing it for decades, and by my time he was the only one who even bid on the Ham at all, unless some Summer Folk who didn’t know the routine butted in, and if that happened, he’d just buy more tickets. So every year, the familiar cry would ring out, “and the Ham goes to Spin!,” and he’d leave early in victory while we all waited around to lose. He kept it in his cellar in a big keg of salt-water, and he’d hoist it up with a meat-hook on the end of a chainfall and cut slices off to make sandwiches or hash. He ate that Ham all the year through, one big, rubbery bite at a time.

Do you know the best part of it? My grandmother said he didn’t even like ham. Not particularly, and she couldn’t blame him. So why did he bet on it, year after year? She asked him once, and he said it was simple. It was a sure thing. It was a thing he could win, and he liked winning and wanted to, and so he did, focusing all his energy on what seemed attainable to him. So, he always won while we all went home empty-handed every time, having squandered our tickets widely on two-dozen lofty chances we were unlikely to attain. In this, dear reader, there is a kind of wisdom and a kind of humor, of that old country sort of which I think our modern world is now in very short supply. Perhaps we’d all be happier, if we took the Ham’s lesson to heart. In any case, it certainly beats hunting from one’s car.

Till next time!