High-tech sensors improve understanding of lakes

TEMPERATURE BUOY in Moose Pond. Colin Holme and Amanda Pratt in front of one of the buoys marking in-lake temperature sensors in Moose Pond.

Using small, digital temperature loggers called HOBO sensors, the Lakes Environmental Association has been busy collecting high-resolution temperature data from many of the lakes and ponds within the area.

Although collecting lake temperature data might not seem novel or particularly high-tech, this new method of sampling is opening up the door to another level of understanding of our lake systems, according to Colin Holme, assistant director of the LEA.

While the LEA has been collecting temperature data on most of the lakes and ponds in this area twice a month from May through September for decades, these new in-lake sensors allow for near continuous monitoring and a greatly extended field season.

According to Holme, LEA’s standard lake monitoring requires staff to go out on the lake and slowly lower a probe down through the water column to get temperature readings. With in-lake sensors, LEA simply installs a string of them in the spring and retrieves the sensors in the fall.

Every 15 minutes, temperature data is recorded by these small waterproof devices and by attaching these loggers every other meter to a buoyed line, a complete picture of the waterbody’s internal structure can be put together.

Because sending staff out in the field is expensive, the LEA was previously only able to attain eight temperature profiles of a lake during a season. This new setup attains 96 of these profiles every day.

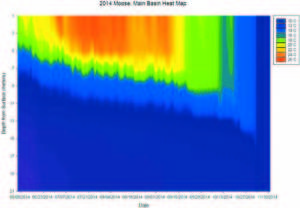

“The best part is that we can continue our sampling very late into the year to see exactly when and how the lake’s summer layering breaks down. We were never able to do this before because many of the deeper lakes don’t ‘turnover’ until late October or November, when our seasonal help is gone and many of our volunteers have pulled their boats,†Holme said.

2014 MOOSE POND HEAT MAP — A heat map of Moose Pond showing temperature variation in the water column over time. The left hand side of the graph shows the depth from the surface, with the top of the graph representing the top of the lake. Lake layering deepens over time (block of color extends further down) until it breaks down. The uniform color on the right side of the graph indicates lake mixing.

In the summer, most of Maine’s deeper lakes stratify into three distinct layers. There is a warm, well-oxygenated upper layer, a middle layer where temperature and pressure change rapidly and the bottom waters are cold and often relatively stagnant as they have no opportunity to mix with the atmosphere. This layering controls where the algae grows, how nutrients move about, the amount of oxygen at different depths and where fish live. Understanding where these layers occur and when they break down is extremely important for understanding lakes.

Holme does not expect these new sensors to replace LEA’s traditional water testing program, as LEA monitors for many other parameters during their twice-monthly sampling. Instead, he hopes it will become another core component of their programming.

“Although the sensors themselves are not expensive, putting strings of them attached to sturdy, marked buoys on a bunch of lakes was not cheap and we could not have done it without the help of local lake associations and grant funding. However, now that we have a system set up and all the gear, we should be able to continue this program for years to come. The amount of information we have already got out of these sensors has been amazing,†Holme said.

In 2014, high-intensity temperature monitoring was done on Back, Hancock, Island, McWain, Moose, Peabody, Sand, Stearns, Trickey and Woods Ponds, as well as Keoka, Highland and Long Lakes.

For more information about this program contact Colin Holme, LEA assistant director at 647-8580 or visit the LEA’s website at www.mainelakes.org